This post is taken from surfiran.com

SHIRAZ TRAVEL GUIDE (UNDERSTAND SHIRAZ)

Shiraz is the capital city of Fars province and a treasure trove of Persian culture. Despite its size, a population of about 1.5 million and an appalling traffic problem, it has retained the relaxed atmosphere of a provincial town, with a university which still retains its reputation.

Many foreign visitors are surprised that the city itself has so few surviving historical monuments when there are such archaeological treasures in the neighbouring countryside, but earthquakes over the centuries have taken a heavy toll.

A settlement from Achaemenid times, it really prospered from the early Islamic era, quickly developing into a walled city. Local disputes between warlords during the 11th—12th centuries caused problems, but Shiraz largely escaped severe damage by the Mongol armies, and its tactical surrender to Timur Leng in 1395 rewarded by great prosperity under his grandson’s governorship.

The good fortune was not to last. In 1668 severe flooding brought death and outbreaks of plague. The citizens had barely recovered when the Afghan rebels, destroying the remnants of Safavid authority, set about massacring the population in 1725. However, under the rule of Karim Khan Zand (d 1779, and still remembered with great affection today) and his descendants, Shiraz regained its former prosperity as the Zand capital for some 20 years in the second half of the 18th century.

Those days of tolerance were short-lived; 15% of the population were Jewish in the early 19th century, but few Jews remain today.

Today it is the place to smell the beautiful Shiraz roses and to buy the perfume and rose-water. Shiraz is also a place to walk in the gardens, see the Azadi Park Ferris Wheel and roundabouts occasionally crowded with excited schoolgirls, their chadors flying in the breeze, or to inspect the carpets in the bazaar.

Both there and in the major shrine, Shah Cheragh, you might glimpse the darker complexions of men and women from various tribal clans such as the Qashqai, the Qash Kuli and the Khamseh, visiting the city. The older men often wear a beige, hemispherical felt cap with a tall upturned rim, while the women cover their immense skirts and glittering lurex tabards with black chadors; both caps and skirts are made in the bazaar. A number of these families still retain a migratory lifestyle, traveling with goats and sheep from Hamadan to Shiraz and the south in late autumn, returning in the spring, but most are now settled in villages nearby. If you want to see the rugs and carpets associated with such clans, Shiraz is the place to look, but prices are no longer cheap and quality is variable since such work was highly acclaimed in the West during the 1976 World of Islam exhibitions in the UK.

GET AROUND SHIRAZ

There is a tourist information on the main boulevard a bit west of the palace. They speak English and can give helpful tips and have English maps.

For non-Iranian visitors, taxis are probably the most convenient mean of transport. However be sure to haggle for a good price prior to getting into the car.

If an unmarked car stops while you are hailing a taxi, don’t be alarmed. Many taxis in Shiraz are unmarked and also as a means to supplement their income, is not uncommon to find private car owners touting themselves as taxis.

Taxi in Shiraz

However it always best to find a taxi through a reputable “telephone taxi” agency. For a set fee, drivers of these agencies will take passengers to their destination, drive them around town and also wait for them while they shop or run errands. All hotels and local residents will have a phone number of one of these agencies. There are also taxis driven by women that specifically cater to women passengers.

The city also has a reasonable bus service.

Train in Shiraz

Shiraz Train station has recently been finished and there are Trains to Tehran but not to Isfahan (Oct 2015). However, the bus journey is shorter (2hrs less), so that might be recommended. There is a connecting bus from the train station to Ghasr Dasht bus and metro station. Price in Aug. 2015 was 10000 real for single ticket.

Metro in Shiraz

The Shiraz Metro is the current rapid transit system in Shiraz, currently operated by Shiraz Urban Railway Organization. Constructions began in 2001, and service in Line 1 was officially commenced on October 11, 2014. Click to see Shiraz Metro Map

WHAT TO SEE IN SHIRAZ

A number of tourist sights in Shiraz are not administered by the central government, so the July 2004 official ruling reducing entry charges for foreign visitors does not apply to these sites.

Quran Gate (Darvazeh-e Quran)

Entering Shiraz from the north, the first visible monument is the Quran Gate (Darvazeh-e Quran), originally built in the 10th century in the city walls. It was Karim Khan Zand who ordered a Quran to be placed in the gatehouse so that all travelers would be blessed as they left for the open road.

In the 1950s increasing motor traffic dictated a new road and the demolition of the gate, whereupon a Shirazi citizen paid for its rebuilding in its present state. Halfway up the hillside, above the gate, is the tomb of one of Shiraz’s famous poets, Khvaju Kirmani (d 1352), and one of the eight known Qajar rock-reliefs, cl 824, showing Fath Ali Shah (d 1834) on a throne dais supported by two angels, with two of his numerous sons in attendance.

Recently, these hillsides have been landscaped with terraces, water cascades and the odd kiosk, and a tea house, the Khajou. While they offer unparalleled views of the city lights at night, the tramp noise and pollution are overpowering. Read more…

Ali Ibn Hamzeh Holly Shrine

Nearby, down from the 18th-century bridge, is situated the Ali Ibn Hamzeh Holly Shrine, constructed perhaps in pre-Seljuk times to honour a relative of the fourth Imam. Its two minarets, exterior dome, entrance vestibule, and courtyard rooms, however, date from the late 18th and 19th centuries. If, as is likely these days, a visit to Shah-e Cheragh shrine is not possible during your stay, this shrine possesses similar extensive Qajar mirror work on its interior walls and vaults.

There is one entrance into the shrine sanctuary (women are asked to don a chador) and as the qibla wall is immediate to the right on entry, one should move quickly to one or the other side to minimize disruption to anyone praying. Read more…

Shah-e Cheragh Shrine

Shah-e Cheragh Shrine is a funerary monument and mosque in Shiraz, Iran, housing the tomb of the brothers Ahmad and Muhammad, sons of Mūsā al-Kādhim and brothers of ‘Alī ar-Ridhā. The two took refuge in the city during the Abbasid persecution of Shia Muslims. The tombs became celebrated pilgrimage centers in the 14th century when Queen Tashi Khatun erected a mosque and theological school in the vicinity.

Shāh-é-Chérāgh is Persian for “King of the Light”. The site was given this name due to the nature of the discovery of the site by Ayatullah Dastghā’ib (the great grandfather of the contemporary Ayatullah Dastghā’ib). He used to see light from a distance and decided to investigate the source.

He found that the light was being emitted by a grave within a graveyard. The grave that emitted the light was excavated, and a body wearing armor was discovered. The body was wearing a ring saying al-‘Izzatu Lillāh, Ahmad bin Mūsā, meaning “The Pride belongs to God, Ahmad son of Musa”. Thus it became known that this was the burial site of the sons of Mūsā al-Kādhim. Read more…

Bagh-e Eram (Eram Garden)

Away from traffic is the beautiful Bagh-e Eram, a garden named after one of the four gardens of Paradise described in the Quran. It is said that the governor of Shiraz visited the Louvre Museum in Paris and accordingly ordered the hike in the entry price. Even though this garden is lovely, it is small and, of course, has no world-renowned antiquities on display, unlike the Louvre.

It was created by a chief of the Qashqai clan around 1823, with a house later rebuilt by Hali Mohammed Hasan Mi’mar with reception rooms, an orangery, stables, and pavilion. Both garden and buildings were confiscated in 1953 and given to the late shah for his private use; this was when the original mud-brick enclosing walls were torn down and replaced by fencing. Later, the university was permitted to establish a botanical garden.

After the fall Of the Pahlavi regime it was returned to the Qashqai family, but then given back to the university, and today it houses the Law Faculty. Sections of the lower garden are out of bounds, and water rarely runs in the irrigation channels, but it is still a lovely place. Most plants and trees are labeled with Farsi, Latin, and common English names. If you are keen on roses, they are in the formal gardens behind the main building. Entry into the building itself is not permitted, but the exterior is photogenic enough with its late- 19th-century tiling under the roof. The main panel shows the legendary Sassanid king, Khosrau, coming across the Armenian princess Shirin bathing while to the right is the Quranic/biblical story describing how the beauty of the prophet Yusuf (Joseph) caused the ladies in Pharaoh’s court to cut their fingers while peeling fruit. Above, the meeting of King Soleyman (Solomon) and the Queen of Sheba, Bilqis, is depicted.

There are three other major gardens in Shiraz but two are 20th-century constructions, owing little to the classic Persian garden layout but pleasant enough now the price for foreigners has been lowered. Read more…

Tomb Of Hafiz (Aramgah-e Hafiz)

One garden surrounds the Tomb Of Hafiz (Aramgah-e Hafiz), the great Shirazi poet (1326—c1390) who wrote lyrical poems about love and the beloved, which are understood to be imbued with deep Sufi mystical meaning; his epithet ‘Hafiz’ alludes to his memorizing of the Quran by heart. Because of this association, one or two dervishes still come here on Wednesdays and Thursdays, while families enjoy the small garden and pleasant late 18th-century (hay-khaneh to the far left. Karim Khan Zand ordered a suitable tomb to be built in 1773 to honour this famous son of Shiraz but that was torn down in 1938 to erect the present octagonal kiosk.

Further embellishments were made for the 1971 Pahlavi extravaganza. Enough said. The bookshop here at the left end of the first porticoed terrace often has a good selection of history and art books in English, as well as maps and postcards, but the English translations of Hafiz on sale render the poetry incomprehensible.

Before leaving, why not have your fortune told? For a small sum, a copy of Hafiz’s best-known anthology, the Divan, will be opened randomly at a page, or a canary plucks out a card with couplets; the verses offer a portent to the future. Read more…

Barm-e Delak

In an easterly direction, some 10km further on, is Barm-e Delak, where there are two battered Sasanian rock reliefs 6m above ground level. The larger one depicts a shah offering a flower to a lady, perhaps the goddess Anahita, though some scholars think this shows Shah Narseh (d301) making a peace offering to the consort of either Bahram Il or Ill. The other panel definitely portrays Bahram Il raising his hand with possibly the influential high priest Kartir to one side. Read more…

The Tomb of Sa’di

The Tomb of Sa’di is set in similar grounds near to the Hafiz garden. Born around 1185 or 1208 (or possibly 1215) and dying around 1292, Sa’di fled the Mongol invasions, going to Baghdad and then Syria where he was imprisoned by the Crusaders. Ransomed by an Aleppan man, he felt duty-bound to marry the man’s daughter, an unhappy decision he commemorated in a couplet:

- A bad wife comes with a good man to dwell

- She soon converts his earthly heaven to hell.

His two major poetic works are the Golestan, a series of anecdotes composed in 1257, and the Bustan (1258) in which he wittily and humorously expounded his thoughts on justice and government.

One of his most famous sayings has prompted comparisons with the 17th-century English poet, John Donne:

- The sons of man are limbs of one another,

- Created of the same stuff, and none other.

- One limb by turn of time and fate distressed,

- The others feel its pain and cannot rest.

- Who unperturbed another’s grief can scan

Is no more worthy of the name of man. A version of this adorns the United Nations building in New York.

Again, the tomb itself is a product of the early 1950s, replacing a Zand structure. If a group has collected in one section beyond the tomb, the probable reason is the underground irrigation channel (qanat) running through the garden, whose water is said to be good for skin problems.

Afif-Abad Garden

Afif-Abad Garden is a museum complex in Shiraz, Iran. Located in the affluent Afif-Abad district of Shiraz, the complex was constructed in 1863. It contains a former royal mansion, a historical weapons museum, and a Persian garden, all open to the public. It’s an old and beautiful garden with its residence in the middle of the city. A very quiet and pleasant place to visit and take lots of photos even for couples. You can also rent traditional clothes for more interesting photos.

Bagh-e Delgosha

Also suggested is the Bagh-e Dalgousha (‘Garden of Heart’s Ease’) nearby. The extensive grounds broadly retain their 1820 layout (actually originally set out in 1790) although the water channels have been relined with tacky turquoise tiles and the original mud-brick walls were destroyed in 2000 for new railings. In the center stands a pavilion from late Zand or early Qajar times, in this dramatic setting with the surrounding hills and tall cypresses. Together with the Bagh-e Eram, this garden and a small one within the newly opened Arg of Karim Khan Zand are the best examples of the ‘classical’ Persian garden outside Mahan and Kashan.

The citadel, Arg-i Karim Khan Zand

The City center The citadel, Arg-i Karim Khan Zand was built around 1767 and is perhaps the best-preserved 18th-century example in Iran. Its use from the 1930s as a police station and prison long prevented access, but in autumn 1999 part of it was opened to visitors. Four 15m round towers with good brick patterning mark the corners of the enclosure joined by 12m high walls which, in Zand times, surrounded an audience hall, barracks, bathhouse, and garden with two pools. When a Qajar prince used the Arg as his official governor’s residence, further building and decoration were undertaken.

Over the main entrance is a huge tiled panel depicting an episode from the Shahnameh in which the famous Persian warrior, Rostam, fights the white Div (demon). The entry vestibule leads into the main Zand court.

A notice in charming, broken English quickly dispels any tiredness and it’s pleasant walking around the central, four-garden layout, noting the original stone water channels in the paving.

Restoration work means it takes but little effort to imagine colorful 18th-century public audiences held under the painted talar verandas, with waterpipes and tea prepared with hot coals from the numerous fireplaces. A suite of rooms which once housed the Cultural Heritage Organisation is now a museum of daily life of the period, complete with atrocious waxwork dummies that completely kill the atmosphere, as do the red ropes limiting free access. The small Hamam near the courtyard entrance, until recently a delightful tea house, is now firmly locked. Nearly all the teahouses are currently shut except for State-operated ones; no reason has been given. Outside, across the street is the small octagonal reception pavilion of Karim Khan Zand, Bagh-e Nazar.

Set in a small garden gloriously smothered in bougainvillea, it offers another peaceful haven away from Shiraz’s traffic and crowds. At its center is an octagonal pavilion, home to the small Pars Museum. Now reopened after restoration, it houses a small collection of mainly 18th- and 19th-century items. Most of its original interior is intact and the tiled panels outside are mainly contemporary with the building. Karim Khan (d1779) must have loved this place as it was chosen as his mausoleum, but he was not allowed to rest in peace. Agha Mohammad Qajar (not known for his generous nature) ordered the remains to be exhumed and sent to Tehran, where they were reburied in the Golestan Palace so that every time the Qajar shah and his ministers crossed the threshold they trod on Karim Khan. At least Reza Shah Pahlavi stopped this practice in 1925, allowing the Zand family to re inter his remains.

Bazaar-e Vakil

Bazaar-e Vakil: The main bazaar area is within walking distance of the Arg. As the name suggests, its construction formed part of the extensive building program undertaken by Karim Khan, so-called vakil (regent) to the last Safavids. Rents from the bazaar and its hamam endowed the Masjid-e Vakil, constructed around 1773, and for many years out- of-bounds to foreign tourists.

It retains a sense of intimacy despite its large size and is organized on the two-ivan plan. Forty-eight stumpy stone columns, each carved in a barley-sugar spiral, mark the sanctuary area. The original mihrab of 1634, which suggested that an earlier mosque had been demolished, is no longer in place, but the 18th-century, 14-stepped minbar cut from one huge block of marble, is.

Some idea of the tile decoration inside can be imagined from the exterior panels. Purists may raise eyebrows at the flamboyant flower motifs and the colorful pastel palette but our spirits soar at such cheerful ornateness. Not all the tiles are original, as some restoration was carried out in 1828 and later years. Next door towards the main road is the bathhouse, converted in 2001 into a tea house and restaurant but now closed by the authorities. It has recently reopened as the private traditional Art & Handicraft Museum so at least the charming interior can still be seen.

Backtracking past the mosque takes you into the carpet section of the bazaar. The Bazaar-e Vakil maintains much of its late 18th-century character with a northeast to southwest orientation (the direction of Mecca) laid out about a century earlier. Originally, it was one long avenue with four large caravanserais to accommodate merchants, but in the 20th century a main road was constructed across the avenue and two of the four caravanserais were demolished in a widening scheme.

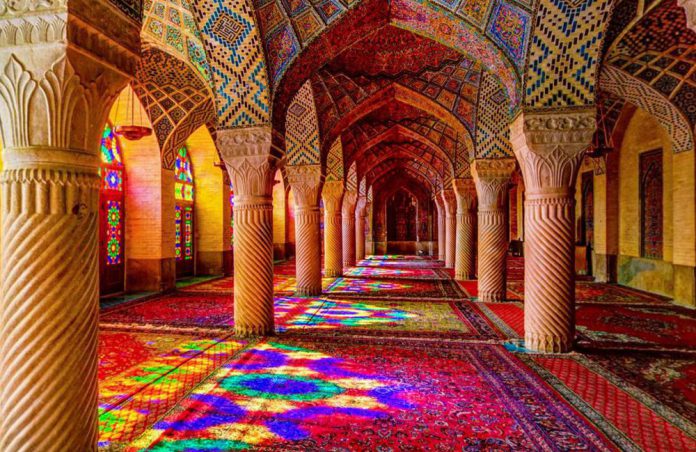

Masjid-i Nasir al-Mulk

Exiting the bazaar by the carpet quarter, turning right and then right again, leads to a charming mosque, the Masjid-i Nasir al-Mulk, rarely visited by tour groups. It is a two-Ivan mosque built 1876—87 by Mohammed Hassan, with a covered arcade on the left (facing the sanctuary) and the winter several synagogues in the city, and Shiraz also has a fire temple.

Persepolis

More than any other ancient site in Iran, Persepolis embodies all the glory — and the demise — of the Persian Empire. It was here that the Achaemenid kings received their subjects, celebrated the new year and ran their empire before Alexander the Great burnt the whole thing to the ground as he conquered the world.

Transport to Persepolis and nearby sites is a problem. There is a scheduled bus service between Shiraz and Marv-Dasht but not to and from Persepolis itself, so the easiest solution is to hire (and retain for the return trip) a taxi, if not from Shiraz (50km southwest) then from Marv-Dasht about 15km away If possible, two visits should be made to the site: in early morning to explore when the light is much ‘whiter’, and about 90 minutes before sunset, when the stone takes on a softer, golden color.

Most of the stone now has a rough grey appearance, a result of wind-blown dust over the millennia, so do make a point of visiting the National Museum in Tehran to see the ‘waxed’ reliefs and column ensemble from Persepolis. This rich, dark brown stone set alongside a creamy limestone was the original coloring.

If you are limited to one visit, it will take three hours or so to walk around and take photographs, especially if you plan to walk up to the Achaemenid royal tombs behind for a magnificent view over the site. Take a telephoto lens or binoculars for viewing these tombs; these will also be useful if you’re going to Naqsh-i Rustam (usually included on the same day).

Naqsh-e Rustam

A 3km drive northwards from Persepolis across the main Shiraz to Isfahan road brings you to Naqsh—e Rustam. Take your binoculars or telephoto lens. The words naqsh (‘picture’) and ‘Rustam’, a legendary Persian warrior, were given to this place by locals seeing the Sasanian rock reliefs of jousting and investiture scenes, but the four Achaemenid tombs carved high into the rock face are more dramatic for today’s visitors.

The first, on the left, was probably the tomb for Darius Il (d405 BCE); the next for Artaxerxes I (d424 BCE); the third and most imposing, held the remains of Darius the Great (d486BCE); and the last, on the adjoining rock face, was carved for Xerxes I (d465BCE) or possibly Xerxes Il (d423BCE). Why the rock face was worked in such a cruciform shape is unclear.

Perhaps it symbolized the empire, covering the four quarters of the known world, the four cardinal points or perhaps an abstract stylization of the Ahura Mazda figure (the head and torso, the protective wings etc). Or perhaps the surfaces were prepared for inscription panels, as at Bisitun, which were never added. As with the Persepolis tombs, the Achaemenid ruler is depicted as if standing above a columned portico, making an offering to the fire altar with the composite Ahura Mazda figure flying above. He stands on a platform held up by representatives of the subject nations.

Before going over to the rock reliefs below the tombs, walk over to the half-submerged stone cube building to appreciate the original ground level. Known locally as the Kaba-e Zardust, it is a single-storeyed building with one entrance and no windows, standing 12.6m high.

Perhaps inspired by earlier (Anatolian) Urartian architecture, it is clearly Achaemenid but its function is a mystery, although it is far better preserved than its Pasargada cousin. It could not have been a fire temple as there is no smoke vent. Perhaps it held royal archives or royal battle standards or served as a mortuary chamber. There is a long inscription along the bottom at the far right of the staircase, but this is Sassanid, added by the High Priest Kartir recording the victories of Shapur I, including his own name wherever possible, stating that he, Kartir, was responsible for establishing fire temples in Cappadocia, Syria, Armenia and Georgia.